Why Does AI Get Things Wrong?

TL;DR;

- LLMs generate text based on statistical patterns learned during training, not by looking up facts like search engines

- They process input as tokens and predict the next most probable token, one at a time, until the answer is complete

- Hallucinations occur because models always try to answer even when uncertain—they can’t know whether they know

- Your prompt matters: too little information causes guessing, too much creates wrong connections

- Models are reliable for common tasks but struggle with uncommon facts, recent events, or poorly documented topics

Most people expect AI tools like ChatGPT to work like Google: ask a question, get a reliable answer. But they’re fundamentally different, and understanding why helps you avoid expensive mistakes.

When you search Google for “population of Edinburgh”, it looks up the answer from indexed sources. When you ask ChatGPT the same question, it doesn’t look anything up. It generates text based on patterns it learned during training. Sometimes that text is accurate. Sometimes it’s confident nonsense.

How LLMs Actually Work

Training is how these models learn. They process millions of documents—books, websites, articles—and learn statistical patterns about which words typically follow others. This takes months of intensive computing. Once trained, the model’s knowledge is fixed until it’s retrained.

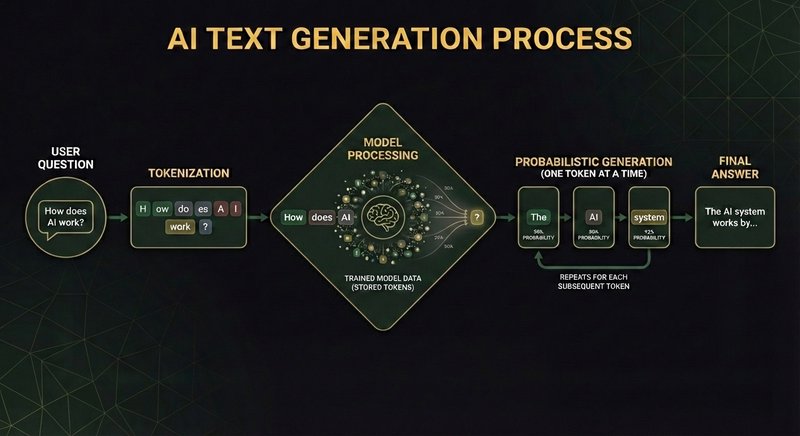

When you ask an AI tool a question, it breaks your text into chunks called tokens. All the data in the model — everything it learned during training — is also stored as tokens and when you submit your question, the model compares your input tokens with what it has stored to generate the first token of a possible response.

Then it applies everything it knows to generate the most probable next token. Then it does the same again for the token after that. And again. And again.

Here’s the process step by step:

- Your input is broken into chunks called tokens—fragments that might be whole words, parts of words, or bits of punctuation

- The model’s data (everything it learned during training) is also stored as tokens

- The model compares your input tokens with what it has stored to generate the first token of a possible response

- It applies everything it knows to generate the most probable next token

- It repeats this process—using all previous tokens to predict the next one—until the answer is complete

What’s remarkable is that when these tools are writing, they’re literally giving you the answer one token at a time based on advanced statistics that predict what’s most likely to come next. There’s no lookup. No consultation of references. Just input tokens going in, output tokens coming out one at a time based on probabilities.

The answer sounds authoritative because those probabilities are well-calibrated — the model was trained on massive amounts of text, so its predictions are often accurate. But it’s still pattern completion, not fact retrieval.

What Does This Mean in Practice?

The model is designed to be helpful. When you ask a question, it always tries to give you an answer—even when it’s uncertain. It can’t say “I don’t know” because it doesn’t know whether it knows. It just generates the most probable next tokens based on what it’s learned.

This leads to hallucinations. The model generates plausible-sounding text that has no factual basis. It sounds confident because the tokens flow naturally, but the underlying patterns are weak or non-existent.

Your prompt matters more than you think. If you give the model too little information, it fills the gaps by guessing—drawing on weak patterns from training data. Ask it to “write a report on our sales performance” without providing actual figures, and it will invent plausible-sounding numbers.

But too much information creates different problems. Overload the model with context, and it can draw wrong conclusions by connecting unrelated details or misinterpreting what matters.

For everyday tasks, the model is often reliable. It knows how to word a polite email because it’s seen thousands of examples. It knows the days of the week, common facts, standard business phrases. The training data for these patterns is extensive and consistent.

It struggles with anything uncommon or poorly documented. Little-known historical facts, recent events that happened after its training, niche technical details, or situations requiring non-obvious inference. The patterns are too weak, so the model guesses. And those guesses sound just as authoritative as the reliable answers.

Things To Try

Same Prompt Different Answers

Ask an AI tool to “draft an email declining a meeting because you’re unavailable”. Then ask the exact same question again in a new conversation. The wording will be different each time—the model picks from multiple plausible options rather than always choosing the highest-probability token. To get more consistent results, use a structured prompt that specifies exactly what you want.

Perplexity - A Different Approach

Perplexity is an AI tool with a difference. Rather than relying on its training data, it runs a lot of searches based on your prompt and then tokenises data scraped from the results and integrates it with the core model to form a reply. This is called Retrieval Augmentic Generation (RAG) and it is often more reliable for research.

Try asking Perplexity about your business or home town and then giving the same question to a general purpose AI like ChatGPT and see if you like the answer from one over the other.

Want to Know More?

Training runs take months and don’t happen often. So how can AI tools answer questions like “What is today’s date?” or “What was the biggest news story yesterday?” when that information obviously wasn’t in their training data.

Ask your AI to explain it with this prompt:

“Explain how AI systems like ChatGPT and Gemini can answer questions like ‘What is today’s date?’ or ‘What was the biggest news story yesterday?’ that could not have been part of their training data.”

Understanding how this works helps you spot when AI has access to current information and when it’s just generating plausible-sounding guesses.

Precision

Precision